Mental health risk assessment is one of the most essential — and nerve-wracking — parts of clinical work. It’s the systematic process of evaluating whether a client may harm themselves or others, and yet even seasoned therapists can feel unsteady when safety concerns arise.

This guide walks you through the tools, questions, and best practices for conducting a thorough mental health risk assessment: from identifying warning signs to documenting safety plans with confidence.

Also, that’s where Mentalyc comes in. As a Clinical Intelligence platform built for therapists, it helps you capture critical clinical data directly from sessions. Its High-Risk Detection feature gently flags concerning patterns and reminds you to create or update safety plans, helping ensure your documentation reflects care, accuracy, and ethical diligence.

What is a Mental Health Risk Assessment? (And Why it’s Not Just About Suicide)

A mental health safety assessment is your structured way of wrestling with two huge questions:

New! Transfer your notes to EHR with a single click. No more copy-pasting.

- How likely is this person to harm themselves or someone else?

- What kind of support is needed right now?

You’re also asking yourself:

- Could they hurt someone else? That might mean lashing out at a family member or someone in their orbit.

- Are they eating? Taking meds? Is where they’re living actually safe?

- Are they taking more chances than usual, substance use, driving too fast?

- Do they seem isolated or confused?

Pro Tip: Conversations about safety are never one-and-done. What someone says this week might shift by next. Keep checking in.

How to Use Key Tools Effectively

| Tool Name | Primary Focus | Best Used In | Approach Type | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) | Suicide ideation and behavior | Outpatient, inpatient, and emergency settings | Structured professional judgment combined with standardized suicide screening tools | Highly validated, easy to administer, suitable for ongoing monitoring | May feel repetitive if used too rigidly; requires clinician sensitivity |

| SAD PERSONS Scale | Quick suicide risk assessment based on demographic and clinical factors | Initial triage, emergency departments | Checklist format | Fast, simple, familiar to many clinicians | Overly simplistic, lacks nuance for individual cases |

| CASE Approach (Chronological Assessment of Suicide Events) | Exploration of suicidal thinking across time | Psychotherapy and crisis intervention sessions | Semi-structured interview | Deep understanding of context and patterns; promotes client trust | Requires time and strong clinical interviewing skills |

| HCR-20 (Historical Clinical Risk Management-20) | Violence risk assessment in mental health and risk management | Forensic, inpatient, and high-risk clinical environments | Structured professional judgment | Comprehensive, evidence-based, widely used internationally | Time-intensive and requires specific training |

| START Manual (Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability) | Clinical risk assessment across multiple domains (violence, self-harm, neglect, substance misuse) | Community mental health and rehabilitation programs | Dynamic and strength-based | Integrates risk and protective factors; promotes recovery-oriented care | Complex to score, moderate research base |

| Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC) | Prediction of short-term aggression or violence | Acute care, inpatient, and emergency settings | Behavioral observation checklist | Quick, practical, and validated for short-term prediction | Limited to immediate (24–48 hours) risk; not for long-term use |

Many of us first learned about safety screening tools in training that felt abstract. But in real practice, they need to feel natural. Here are a few that can help you get your footing.

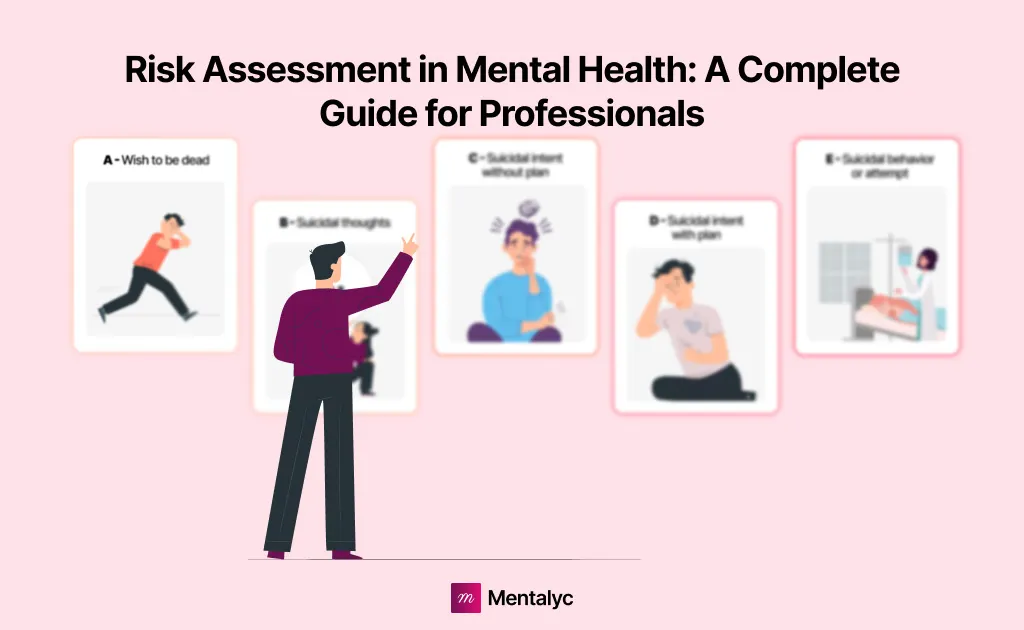

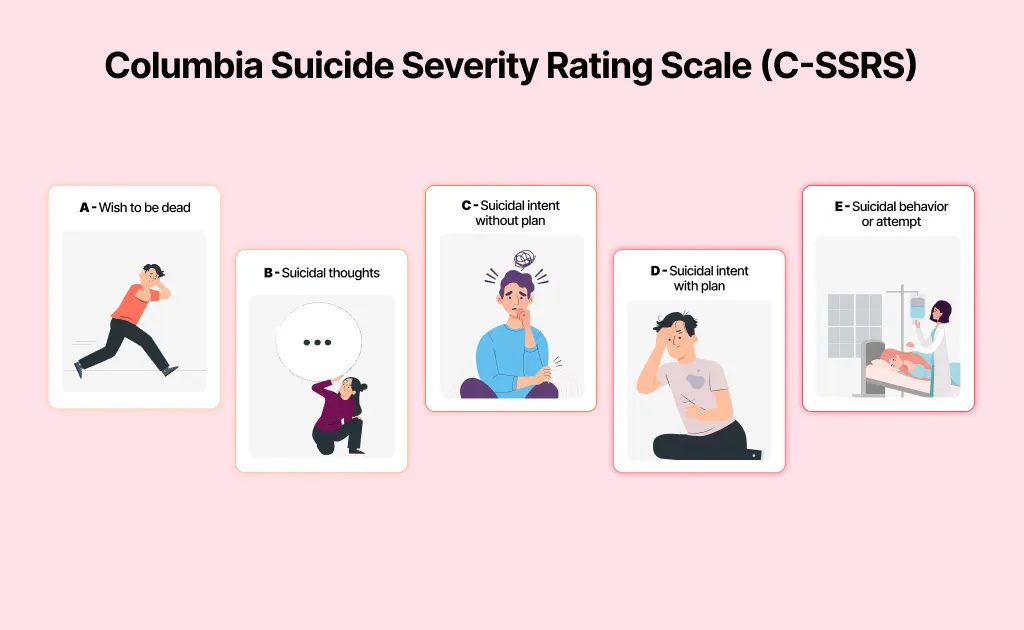

The Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

If the C-SSRS assessment isn’t in your rotation yet, it’s time to change that

Here’s the thing about using it well:

- Don’t run down the list like a script. Rather than reading straight from a form, follow the conversation. If a client says they’ve been feeling stuck, that’s a moment to lean in a little. You might say, “Sounds like things have been heavy. Have you ever had thoughts about not wanting to be around anymore?”

- Pay attention to where they land on the spectrum. The C-SSRS lays out how thoughts can move from vague unease to concrete planning. That helps you determine whether this is something to track, or act on now.

- Use behavioral markers. Don’t just focus on words. Have they made a plan? Given away belongings? Researched methods? These actions tell you just as much as the conversation.

The CASE Approach: For When You Need More Depth

The CASE Method (Chronological Assessment of Suicide Events) helps explore someone’s suicidal thinking across time. What’s changed? What patterns are emerging? Where’s the progress? The CASE approach is particularly helpful when you’re working with clients who’ve been struggling for a long time with suicidal thoughts and need a space to unpack, not just report. This method can strengthen your self-harm assessment process by identifying shifts in intent and coping.

Key Reminders

Intent doesn’t always match lethality. Someone might be determined, but choose a method that’s unlikely to be fatal. Others might act impulsively with dangerous means. Ask about both.

The “I Won’t Do Anything” Promise: Getting clients to promise they won’t hurt themselves isn’t protective or productive. What is protective? Collaborative safety planning. This planning gives them specific alternatives for when they’re in crisis.

Common Mistakes (That We’ve All Made)

The “They Seem Better” Trap: Risk can increase when depression starts lifting because the person has more energy to act on suicidal thoughts. Don’t decrease monitoring just because a client’s mood improves.

The Hospitalization Reflex: When a client shares thoughts of distress or hopelessness, inpatient care may not always be the most appropriate or helpful response. You may also risk damaging therapeutic relationships and creating unnecessary trauma.

The Documentation Disaster: Writing “low risk” without explaining why. Your future self (and possibly lawyers) need to understand your reasoning.

The Resource Assumption: Assuming clients have social support, transportation, or financial resources they don’t have. Always assess for practical barriers to safety during any violence risk assessment mental health process.

Common Tools Used in Mental Health Risk Assessment

These are the tools clinicians often reach for in everyday practice:

Quick Screening Tools (Typically finished in 2-3 minutes)

SAD PERSONS Scale

- The Basics: 10-item checklist, quick scoring system

- Best Settings: Emergency screening, triage situations

- Strengths: Fast, easy to remember, good for newer clinicians

- Limitations: Oversimplifies complex risk, limited predictive value for individuals, works primarily for initial screenings

What it stands for:

Each letter in SAD PERSONS stands for:

S – Sex

A – Age (under 19 or over 45)

D – Depression or feelings of hopelessness

P – Previous suicide attempt

E – Excessive alcohol or substance use

R – Loss of rational thinking (e.g., due to psychosis or illness)

S – Lacks social support

O – Organized or serious suicide plan

N – No partner (single, divorced, or widowed)

S – Sickness (chronic or terminal illness)

Brøset Violence Checklist (BVC)

- The Basics: 6 behavioral observations, simple yes/no format

- Best Settings: Inpatient units, emergency departments

- Strengths: Quick, observation-based, reasonable short-term prediction

- Limitations: Only predicts next 24-48 hours, requires direct observation

Comprehensive Assessment Tools (Can range from 10-90 minutes)

Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

- Best Settings: Most clinical settings when you need standardized assessment

- When to Use: Initial screenings, tracking changes over time

CASE Method

- Best Settings: Outpatient therapy sessions

- When to Use: When you need a deeper understanding

HCR-20 (Historical Clinical Risk Management-20)

- The Basics: 20 items across three domains, structured professional judgment

- Best Settings: Forensic units, specialized violence assessment programs

- Strengths: Comprehensive, well-validated, includes risk management factors

- Limitations: Training-intensive, time-consuming, requires significant clinical experience

The HCR-20 risk management process supports structured decision-making and helps ensure that high-risk cases receive appropriate intervention.

Specialized/Multi-Risk Tools (Generally around 30-45 minutes)

START (Short-Term Assessment of Risk and Treatability) Manual

- The Basics: 20 dynamic factors, covers multiple risk domains

- Best Settings: Community mental health, case management programs

- Strengths: Addresses multiple risks simultaneously, including protective factors

- Limitations: Complex scoring, requires training, still developing research base

Top Tip: Start with one tool you can use confidently. Build from there.

Making Documentation Easier

Wish you had a form that wasn’t overwhelming? Use this template to document clearly:

CLIENT INFORMATION

- Name: DOB:

- Date of Assessment: Time:

- Evaluated by: Setting:

- Reason for Assessment:

CURRENT PRESENTATION

- Current mental state:

- Presenting concerns:

- Recent stressors/triggers:

- Substance use (current):

RISK ASSESSMENT

Suicide Risk:

- Current suicidal ideation: □ None □ Passive □ Active

- Details of plan and means access: □ Yes □ No Details:

- Previous attempts: □ Yes □ No When/How:

- Protective factors:

Violence Risk:

- Thoughts of harming others: □ Yes □ No

- Specific targets:

- History of violence: □ Yes □ No Details:

- Current triggers:

Self-Care/Neglect Risk:

- Medication compliance: □ Good □ Poor □ N/A

- Basic self-care: □ Adequate □ Concerning

- Living situation safety: □ Safe □ Unsafe

- Details:

PROTECTIVE FACTORS

- Social support:

- Coping strategies:

- Reasons for living:

- Treatment engagement:

CLINICAL TOOLS USED

- C-SSRS Score:

- SAD PERSONS Score:

- Other:

RISK LEVEL DETERMINATION

- Low Risk, Moderate Risk, High Risk

- Rationale:

IMMEDIATE INTERVENTIONS

- Safety planning in therapy, Increased monitoring, Hospitalization

- Crisis team contact, Family notification

- Specific actions:

FOLLOW-UP PLAN

- Next contact:

- Frequency:

- Specific monitoring:

ADDITIONAL NOTES

CLINICIAN SIGNATURE & DATE

Documentation Example – Key Fields:

Here’s a helpful clinical documentation example to illustrate clear reasoning:

Mental state: Depressed, tearful, low energy, hopelessness present

Current ideation: Passive “Sometimes think everyone would be better off without me.”

Risk determination: Moderate Risk

Rationale: Passive suicidal ideation with multiple stressors but strong protective factors. No intent or plan. Increased alcohol use concerning.

Actions taken: Safety plan completed, excess medications removed, sister to check daily, crisis line number provided

Clinical Documentation from the Frontlines: The Nursing Perspective

Nurses often catch the first signs that something’s off, changes others might miss in passing. You’re watching for subtle shifts in how someone moves through their day, what’s said (and unsaid), and how their body responds to stress.

Here are just a few things nurses tend to notice early:

- A client who stops eating regularly or isn’t sleeping well

- Missed medication doses, side effects, or new reactions

- Agitation that builds slowly between formal evaluations

- Family visits that seem to spark distress or withdrawal

When you’re documenting, go beyond vague phrases like: “appeared anxious.” Instead, try something like, “Client avoided eye contact, sat with arms crossed, voice shook while discussing discharge plans.”

NICE Guidelines (UK): What You Need to Know

The UK’s NICE guidelines for clinical risk assessment emphasize several key points that apply universally:

1. Structured clinical judgment over actuarial tools – Use tools to inform, not replace, clinical thinking

2. Routine inquiry about suicidal thoughts – Ask everyone, not just high-risk clients

3. Consider protective factors alongside risk factors – What’s keeping this person safe? What are their triggers?

4. Document rationale for decisions – Explain your clinical reasoning

5. Regular review and reassessment – Risk changes over time

Building Your Process

1. Preparation

Know your local crisis numbers ahead of time, and clarify what your clinic or team expects if things become urgent. When something escalates, that’s not the moment to go hunting through a binder.

2. Systematic Inquiry

- Begin broadly, then focus specifically

- Integrate structured tools naturally into the conversation

- Explore risk factors alongside protective factors

3. Clear Decision Making

- Low risk: Basic safety planning

- Moderate risk: Increased contact frequency, specific interventions, family involvement

- High risk: Immediate safety measures, possible hospitalization consideration

These steps together form a therapist safety checklist for consistent responses.

When Things Go Wrong: The Hard Conversations

Sometimes, things go sideways. You might’ve felt confident about where someone was at; maybe they seemed grounded, even optimistic, and then something shifts. People are complicated, and outcomes don’t always follow logic or effort.

Remember this:

- You’re not being asked to predict what happens next, just to respond with care, clinical reasoning, and clarity.

- Reach out for help. Supervision isn’t a luxury; it’s protection.

- Take care of yourself. Clinical work around safety is heavy. Don’t carry it solo.

Implementation Checklist You Can Use

Before Assessment

Review available background information

Prepare assessment tools and ensure privacy

Consider environmental factors

During Assessment

Build rapport and begin with open-ended questions

Assess multiple risk areas and protective factors

Include client in risk level determination

After Assessment

Document observations and clinical reasoning

Complete safety planning if needed

Schedule appropriate follow-up

The Bottom Line

No checklist makes this work easy. Risk assessment in mental health is about showing up fully, asking hard questions, and making your best call, sometimes with your gut in knots. You won’t always have a clear answer. There won’t always be a clear answer. You may leave some sessions wondering whether you did enough, and that uncertainty is part of the work. What matters most is staying present, asking thoughtful questions, and offering steady care in moments that are rarely simple.

With Mentalyc, you don’t have to rely solely on memory or scattered notes. It automatically captures key clinical information from each session, including potential risk indicators, and reminds you when a safety plan needs attention. So even in the toughest cases, you can trust your documentation to reflect the same care and precision you bring to your clients.

Mentalyc Plans & Pricing

| Plan | Price | Key Features |

| 14-Day Free Trial | $0 | 14 days of full PRO access, including 15 notes—no credit card required. |

| Mini | USD 14.99 /month | Record in-person sessions, upload audio files, use voice-to-text, or type notes directly, etc |

| Basic | USD 29.99 /month | Everything in Mini, plus: Alliance Genie™ NEW! (limited access), Smart TP™ |

| Pro | USD 59.99 /month | EMDR, Play and Psychiatry modalities,100+ custom templates incld. BIRP, PIRP, GIRP, PIE, and SIRP, Auto-computed CPT codes |

| Super | USD 99.99 /month | Everything in Pro, plus: Group therapy notes for each group member, Priority onboarding and support |

For more information, visit the pricing page on our website.

FAQs About Risk Assessment and Navigating Safety in Mental Health

How to Conduct a Suicide Risk Assessment?

A suicide risk assessment involves combining suicide screening tools with open, empathic dialogue to understand a client’s level of distress and potential danger. Clinicians use suicide risk assessment tools such as the C-SSRS or SAD PERSONS scale to identify key factors—ideation, intent, plan, and protective supports. The process also involves assessing intent and means, evaluating access to lethal methods, and exploring coping strategies. Effective suicide risk assessment requires structured professional judgment, balancing evidence-based measures with clinical intuition and contextual understanding.

What are we really doing when we assess risk?

You’re not just completing a form. You’re trying to understand where someone’s at, what’s rising beneath the surface, and what kind of care fits best right now.

Why are mental health risk assessments so important?

In a crisis, guessing your way through isn’t enough. A solid risk assessment helps you catch changes early, identify what’s being built, discern what’s being said between the lines and determine how to respond before it escalates. It’s how we show up fully for our clients and protect their safety.

What kinds of risks should I assess?

You’re looking at more than just suicide risk, though that’s huge. You’re also watching for:

- Whether they might hurt themselves

- Signs they could harm someone else

- Keep an eye on the basics: Are they getting enough to eat? Sleeping? Taking their medications as prescribed?

- Watch for impulsive decisions, as these can put them in danger quickly.

- Check for vulnerability: are they in environments or relationships where someone might take advantage of them?

What tools should I use for risk assessment?

Go with what works in your setting and feels natural to use:

- C-SSRS: Reliable for suicide risk, especially when it’s part of a real conversation.

- SAD PERSONS: Super quick in a pinch; just don’t let it be the only thing you rely on.

- CASE: Really useful when someone’s been dealing with suicidal thoughts for a long time.

- HCR-20, START, and Brøset: You’ll see these more in hospitals or forensic units. You’ll need some training, but they’re strong frameworks when used right.

None of them replace your judgment. They just help organize it.

What Are the Best Practices for Documenting Risk Assessments?

Best practices emphasize clarity, context, and rationale. Documentation of suicide risk should detail what was assessed, how conclusions were reached, and what steps were taken to ensure safety. Include both risk and protective factors, describe interventions, and justify your clinical reasoning documentation. Good notes reflect what was said, what actions were taken, and the reasoning behind your level of concern. Clear, timely, and defensible documentation also strengthens collaboration within multidisciplinary clinical decision-making teams.

What Is the Role of Risk Assessment in Nursing and Frontline Care?

In frontline and therapeutic risk management, nurses often serve as the first point of contact for identifying early warning signs of suicide or self-harm. They notice subtle changes, like sleep disruption, withdrawal, or medication noncompliance, that may indicate rising risk. Their assessments often guide crisis de-escalation strategies and ensure prompt communication with the wider care team. In this setting, accurate observation and timely escalation of concerns are key components of safe and responsive mental health practice.

What are The NICE Guidelines for Mental Health Risk Assessment?

The NICE Guidelines for mental health risk assessment recommend integrating trauma-informed safety assessment with evidence-based tools and compassionate inquiry. Clinicians should not rely solely on checklists but instead combine clinical observation with contextual insight. NICE emphasizes balancing risk and autonomy, encouraging clinicians to involve clients in decisions that affect their care while maintaining safety. Regular ongoing risk monitoring ensures assessments remain current as circumstances evolve.

How to Create a Collaborative Safety Plan?

A collaborative safety plan is a cornerstone of crisis intervention planning and recovery-oriented care. It’s built with the client, not for them, by identifying triggers, warning signs, coping skills, and supportive contacts. Effective safety planning in therapy focuses on empowerment, providing clear, step-by-step actions clients can take when they feel unsafe. It’s most effective when revisited regularly, adjusted as progress occurs, and integrated into broader treatment goals for stability and resilience.

How do assessments guide care?

They won’t always give you a clear yes or no, but that’s not the point. What they do offer is direction. Maybe it’s a sign to check in more often, bring in a family member, work on a safety plan, or call in extra support. Whatever the next step is, you’ll have something solid to base it on.

What if I’m not sure what to do?

Checking in with a supervisor or peer can offer the clarity you need to move forward with confidence.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2023, February 22). Screening for suicide risk in clinical practice. American Academy of Pediatrics.

Assessment and management of patients at risk for suicide. (2019). VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Chaplin, S. (2023). NICE on the assessment and management of self-harm. Prescriber, 34(1), 21–22.

Clinical guidelines on risk assessment. (2025). National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Safety in Mental Health.

Conlon, D., Raeburn, T., & Wand, T. (2024). Mental health risk assessments of patients, by nurses working in mental health settings: a qualitative study using cognitive continuum theory. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 45(5), 488–497.

Fedorowicz, S. E., Dempsey, R. C., Ellis, N., Phillips, E., & Gidlow, C. (2023). How is suicide risk assessed in healthcare settings in the UK? A systematic scoping review. PLOS ONE, 18(2), e0280789.

How and when are risk assessments required to be performed? (2025). The Joint Commission.

Janssen. (2012). Mental Health Assessment Tools. In Drugs and Alcohol Information and Support.

Large, M., & Nielssen, O. (2017). The limitations and future of violence risk assessment. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 25–26.

Matthewson, P. (2016). Risk assessment and management in mental health.

Mental Health Assessment Tools and Apps for Nurses (with Examples). (2024, April 16). Medesk.

Mental health risk assessment: Traps to avoid in day-to-day clinical work. (2019, October 11). Psych Scene Hub.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022a). Self-harm: Assessment, management and preventing recurrence. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2022b). Self-harm: assessment, management and preventing recurrence NICE guideline.

NICE guidelines developed by NCCMH. (2025). Royal College of Psychiatrists.

NICE social care mental health guidance. (2025).

Puchkors, R., Saunders, J., & Sharp, D. (2023). Risk and protective factors of mental health. OpenStax.

Risk assessment: START manuals. (2024). BC Mental Health & Substance Use Services.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2016). Assessing and managing risk of patients causing harm.

Screening for suicide risk. (2016). Zero Suicide.

Screening Tools for Suicide Prevention. (2022). Rural Health Information Hub.

Simmons, K. (2021). Module 5: Assessing risk. Counseling and Assessment Clinic.

Suicidal Ideation and Behavior – C-SSRS Screening Questions. (n.d.). In Prevent Suicide NY.

Tariq, S., Prasanna, A., & Lau, R. (2024). Assessment of Compliance With NICE Guidelines on Safety Planning Following Self-Harm in Elderly Patients in a Mental Health Trust. BJPsych Open, 10(S1), S265–S265.

The strengths and limitations of risk assessment. (2015). Center for Justice Innovation.

White paper: On the principles of mental health risk assessment. (2024). In Victoria State Government Department of Health.

Why other mental health professionals love Mentalyc

“Having Mentalyc take away some of the work from me has allowed me to be more present when I’m in session with clients … it took a lot of pressure off.”

LPC

“It takes me less than 5 minutes to complete notes … it’s a huge time saver, a huge stress reliever.”

Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

“It’s so quick and easy to do notes now … I used to stay late two hours to finish my notes. Now it’s a breeze.”

Licensed Professional Counselor

“By the end of the day, usually by the end of the session, I have my documentation done. I have a thorough, comprehensive note … It’s just saving me hours every week.”

CDCII